Similar to an LLC, an S-Corp can be composed of a single shareholder or multiple shareholders. However, being a corporation, the S-Corp must file Form 1120S (U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation) and issue K1’s even if it has only one shareholder. S-Corp shareholders have several unique restrictions. For example, shareholders must be an individual and cannot be another entity like another corporation or an LLC. The individual needs to be a U.S. citizen or a resident alien and the S-Corp cannot exceed 100 shareholders. That said to truly understand how you get paid an Officer and Shareholder or Just a Shareholder of an S-Corp there are a few concepts that we need to cover first.

The Truth About Why Draws and Distributions Are Non-Taxable

Most small business founders choose one of the many entity types known as pass-through entities. By definition, a pass-through entity is not subject to income taxes at the entity level. Rather, the owners are taxed individually based on their ownership share of the business.

When you are a pass-through entity, the profits of a business are taxable to the individual owners based on their unique tax situation. Often these owners will take cash out of the business as compensation in the form of periodic draws or distributions.

Assuming you have a profitable business, these draws and distributions are simply a mechanism that allows owners to take out excess cash from the business. Therefore, owner draws and distributions do not have any income tax consequences to the individual.

This concept often creates a level of confusion for founders not versed in a few basic principles of accounting. To understand the concept of an owner-draw or distribution, we must review a few basic accounting principles.

There are 2 primary financial statements for every business. One statement is the Profit & Loss (P&L), sometimes called an income statement. The other statement is a balance sheet. The P&L is a document to record the profit or loss of a business for income taxes while the balance sheet is a document to record the equity in the business.

In accounting, a company has what are known as a chart of accounts. Some chart of account line items are classified as income accounts and some others as expense accounts. Income accounts and expense accounts are reported on the company’s P&L. If you take income and subtract expenses, you are left with net profit, which is also part of the company’s P&L.

P&L (Revenue – Expenses = Net Profit)

Another set of chart of accounts are classified as asset accounts and others as liability accounts. Assets accounts and liability accounts are reported on the company’s balance sheet. If you take your assets and subtract your liabilities, you are left with equity, which is also part of the company’s balance sheet.

Balance Sheet (Assets – Liabilities = Equity)

In accounting, for every transaction, there is a debit and credit taking place between two charts of accounts.

When you write a company-check to pay a bill, such as when you buy some business books, you take money from a chart of account line item called cash (Cash is an asset and lives on your balance sheet) to pay a bill that lives on your P&L. Bills are allocated to their appropriate expense chart of account line item.

Since you reduced cash on your asset chart of account, equity is also reduced to keep things in balance. Equity has to be reduced because it is the result of your assets minus your liabilities. Additionally, since the cash was used to pay an expense your profit is also reduced. Profits must be reduced because it is the result of income minus expenses.

However, when you take an owner draw or a distribution, you reduce cash (an asset chart of account) and you reduce the owner’s capital (a special equity chart of account). Similarly, if you inject cash into a business, you increase cash and increase the owner’s capital.

The results of an owner-draw or distribution (money leaving the business) or a cash infusion (money entering the business) are that both sides of the transaction are restricted to the chart of accounts that live only on the balance sheet.

Since we know that the P&L is used to compute a company’s tax liability and owner draws, and distributions or infusions do not touch the P&L, there are no tax consequences for doing either an owner draw, distribution, or a cash infusion in the normal course of business. An exception is when you close out the business and have a negative equity situation but that is the subject better left to your CPA.

Therefore, as a lifestyle or micro business, you only need to make sure there is enough cash in the business checking account to cover all non-discretionary expenses. All other money is at your discretion to either take out as a periodic owner draw or distribution on profits or to leave in your business as excess cash or use to pay discretionary expenses in the hopes of growing your business.

How to Get Paid as an Owner of a Pass-Through Entity

In my practice as a small business coach and mentor, a question I often get asked is how do I get paid as a business owner? What makes this question so hard to answers is that it all depends on the type of entity you are and how many owners there are.

Some entities have only one owner while others may have several owners, which changes the way income tax is reported to the IRS.

In a pass-through entity, sometimes income is considered earned income (sometimes called ordinary income or active income) while other times it is considered passive income, which changes the way income taxes are computed.

Your role in the business as a decision-maker (manager/officer) or a simple investor (member/shareholder) will define how your income taxes are calculated.

Income tax treatment, therefore, will dictate the way you will get paid as an owner.

What Is a Pass-Through Entity?

Most small business founders choose one of the many entity types known as pass-through entities. By definition, a pass-through entity is not subject to income taxes at the entity level. Rather, the owners are taxed individually based on their ownership share of the business in a tax-advantaged way. The only entity not considered a pass-through is the C-Corp.

How to Report the Profit and Loss of Business

A company should have a Profit & Loss (P&L), or income statement, which is an internally prepared tax document that is used by the business to compute the business owner(s) annual tax liability.

When the business is an S-Corp, the P&L is used to produce Form 1120S. The 1120S is an informational tax return that is sent to the IRS. The business will also produce K1’s that are sent to each owner.

What Is Passive Income vs. Earned Income?

When the income derived by the business comes as the result of some form of labor, then the income is classified as earned income. Earned income is subject to FICA (Social Security) and Medicare taxes.

However, sometimes income from the business does not involve labor, such as when a business’s income comes from charging rent to a tenant. When the income is not the result of labor, the income is considered passive income, and as a result, it is not subject to FICA or Medicare taxes and is reported on Schedule E of the individual’s 1040 tax return.

Even within a single entity, the income for one owner may be considered earned income while another owner’s income might be considered passive income. The distinction comes if the individual owner either works more than 500 hours in the business or is in a management position and makes day-to-day decisions for the business.

When an owner’s income is considered earned income, that owner has some options for tax deductions such as healthcare or retirement contributions that owners who receive passive income do not. Of course, the owners with earned income then subject that income to FICA and Medicare taxes.

What Are Self-Employment (SE) Taxes?

As an employee, we are used to having 7.65% deducted from our net income as our part of our FICA and Medicare tax contributions. What you don’t see as an employee is that the employer is obligated to match your FICA and Medicare tax contributions.

When your income from the business is considered earned income (therefore subject to FICA and Medicare taxes) and you are also an owner of the business, then you are both the employee and employer in the eyes of the IRS. As a result, you must pay both the employee and the employer portions of FICA and Medicare taxes. When we talk about self-employment or SE taxes, we are including both the employee (7.65%) and employer (7.65%) portions of the FICA/Medicare contribution for a total of 15.3%.

How to Get Paid as an Officer and Shareholder of an S-Corp

Being a corporation, the S-Corp must file Form 1120S (U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation) and issue K1’s even if it has only one shareholder. S-Corp shareholders have several unique restrictions. For example, shareholders must be an individual and cannot be another entity like another corporation or an LLC. The individual needs to be a U.S. citizen or a resident alien and the S-Corp cannot exceed 100 shareholders.

An S-Corp, however, is still a pass-through entity and will submit an informational return to the IRS known as Form 1120S. Each of the shareholders will be issued a K1. The K1 for each owner will designate how the owner’s share of income, deductions, and credits are allocated for tax purposes on their personal 1040 tax return. To be clear, while an individual is responsible for paying the taxes for a profitable business, the business does not have to physically write the shareholders a distribution check for the full amount of the company’s profits. In fact, it is advisable that some of the profits be retained by the business to cover future expenses and provide capital for growth.

For my shareholders, I would generally issue a distribution to cover the shareholder’s tax obligations and retain the rest to reinvest in the business. What differentiates the S-Corp from its LLC and partnership cousins is that in an LLC or partnership all the income for an active member or partner is usually considered earned income, 100% of which is subject to self-employment taxes. However, with an S-Corp some of your income can be treated as earned income and taxed accordingly while some income can usually be considered passive income and avoid FICA and Medicare tax contributions.

In an S-Corp, the shareholders elect the board of directors to represent the interest of the shareholders. The board of directors, in turn, hires officers to run the day-to-day operations of the business. The officers can be shareholders but they do not have to be. The IRS considers officers employees of the S-Corp. Moreover, the IRS requires that officers receive a reasonable salary. As with any salary, the salary that the officer receives is subject to FICA and Medicare taxes. The officer’s salary is an expense to the corporation and reduces the S-Corp’s taxable income. At the end of the year, the officer will receive a W2 stating his reported salary and FICA and Medicare contributions so that the officer can use it to report their W2 salary income on their individual 1040 tax return.

The net profit of the S-Corp, after the officer’s salary and payroll taxes (matching FICA and Medicare tax and unemployment taxes), is deducted, are reported on the K1 issued to shareholders. The K1 is used by the shareholders to report their income/loss on their Schedule E (supplemental income and loss) of their individual 1040 tax return. Throughout the year, the shareholders can take non-taxable cash distributions of the profit since all profits of the S-Corp will be taxed on the shareholder’s individual tax returns through their Schedule E.

In many S-Corps, the officer is also a shareholder. So, while all of the officer’s income from wages or salary and their profit share is subject to federal and state income tax based on the officer’s marginal income tax rate, the portion of their income that comes from their profit share is not subject to self-employment taxes (the combined employer or employee share of FICA and Medicare), thereby saving 15.3% in taxes.

Let’s compare the tax consequences of a single-member LLC to a single shareholder S-Corp. To keep it simple, let’s assume you are in a non-construction-related business, your effective combined federal and state income taxes amounted to 30%, your total business income was $100k, and a reasonable salary for a person doing your job was $50k.

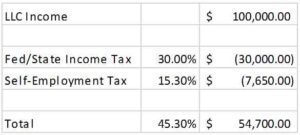

LLC:

In an LLC, your tax rate would be 45.3% (30% federal/state plus 15.3% for self-employment tax that is made up of both the employer and employee share of FICA and Medicare). Your after-tax income would be $54,700 since 100% of your compensation is taxable and subject to self-employment taxes. Simple but not very tax efficient.

S-Corp:

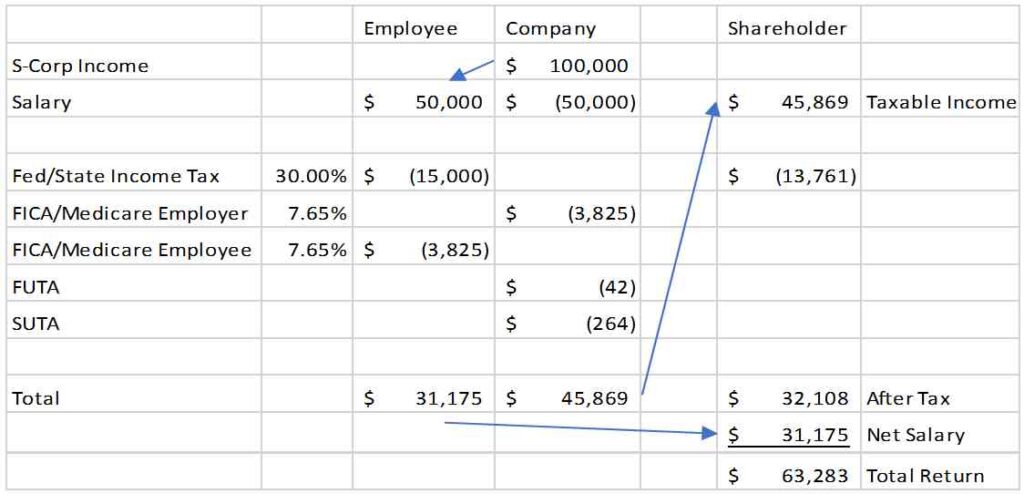

As an S-Corp, we have to consider the tax consequences for you as an employee, the S-Corp, and then as the shareholder. Let’s look at each condition.

S-Corp Officer Salary (Employee):

In an S-Corp, the first $50K in our example would be considered salary since this was considered a reasonable compensation for a person performing these duties as an officer in your industry. As an employee, you would be subject to federal and state withholding plus your share of FICA and Medicare only. So, the first $50k is subject to 37.65% (combined tax rate of 30% federal/state plus 7.65% FICA and Medicare) in taxes. Your after-tax income would be $31,175 as an individual officer/employee of the business. These totals would be reported at the tax year-end through a W2.

S-Corp Company:

The S-Corp would be responsible for the 7.65% FICA and Medicare match for your $50k Salary. The corporation would deduct your $50k in salary plus the $3,825 (7.65% FICA/Medicare) match and make the deposits on your behalf for the $15k in federal/state withholding plus $7.65k (both halves of the FICA and Medicare tax).

The IRS and the state consider your salary covered under the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) and State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA). For FUTA, the S-Corp must pay an additional .6% of payroll for the first $7k only ($42 in our example). SUTA varies by state and often varies by occupation. SUTA is usually covered by the employer in most states. In Colorado, where I live, the first $12,500 in salary is subject to SUTA and the tax rate for non-construction occupations is 2.11%. Where there is heavy construction, it is 9.57%. Since in our example we are a non-construction-related business, the SUTA would be $264.

So, the S-Corp would deduct the $50,000 Salary and the $3,825 in its employer FICA and Medicare contribution match. It would also be obligated to pay the $42 FUTA and $264 SUTA which are considered expenses to the business and therefore also deductible. Collectively the FICA and Medicare match and FUTA and SUTA are called payroll taxes in accounting parlance.

The net profit of the S-Corp that it would put on its Form 1120S would be $45,869. Since there is only one stockholder (you), the K1 would allocate the entire $45,869 in taxable income to you as the only shareholder.

Shareholder:

Your 100% share of the S-Corp’s net profit is $45,869 and is considered taxable income. Being unearned income, the net profit is usually only subject to the 30% federal/state taxes ($13,761) so your after-tax income would be $32,108. As we discussed in the post “The Truth About Why Draws and Distributions are Non-Taxable”, shareholders may take periodic profit distributions of the taxable income which are not tax-deductible to the business but reduce the shareholder’s equity. However, when it comes to taxable income, in our example $45,869, the onus is on you to estimate the taxable income you will receive throughout the year and then make quarterly deposits to the IRS using Form 1040-ES to cover your anticipated annual tax liabilities. The same is true for your estimated state taxes. To avoid IRS penalties, your tax estimates should add up to at least 90% of your estimated tax liability.

In the end, you would earn $31,175 in after-tax salary as an employee. The S-Corp would be able to deduct the $50,000 in salary and $3.875 in its FICA and Medicare match. Also deductible is the $42 FUTA and $264 SUTA it was obligated to pay, leaving $45,869 in net profit. As a shareholder in our example, your taxable income of $45,869 is subject to your 30% federal/state taxes only since the income is considered passive income, leaving you with $32,108 in after-tax income. When you combine the $31,175 in after-tax salary earned as an employee and add the $32,108 in taxable income you earned as a shareholder, your net after-tax return is $63,283.

Even though your taxable income as a shareholder is $32,108, it is not wise to distribute 100% of the profits to the shareholders. The business should leave some of the equity in the corporation as there needs to be sufficient capital to cover any net loss the company may incur in the future and to provide the needed capital for growth. So, in our example, with an LLC you would net $54,700 while in the S-Corp you would net $63,283, a difference of $8,583. After all, it is not how much you make from your business but how much you get to keep in the end that counts.

Example Summary

In summary, as an officer and shareholder, the S-Corp would issue you a W2, reflecting $50,000 in gross salary, and your $18,825 (the sum of federal/state income tax plus your FICA and Medicare) in withholdings in our example. Then, the S-Corp would file its Form 1120S showing a net profit after deductions, $45,869 in our example.

The S-Corp would issue you a K1 showing your share of the S-Corps net profits, $45,869 in our example since you were the only shareholder. As a shareholder, you would record your share of the net profits on your Schedule E of your 1040 personal tax return. Since this portion of your income is usually considered passive income, you are not subject to self-employment taxes.

How to Get Paid a Shareholder of an S-Corp

Similar to an LLC, an S-Corp can be composed of a single shareholder or multiple shareholders. However, being a corporation, the S-Corp must file Form 1120S (U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation) and issue K1’s even if it has only one shareholder. S-Corp shareholders have several unique restrictions. For example, shareholders must be an individual and cannot be another entity like another corporation or an LLC. The individual to be a U.S. citizen or a resident alien and the S-Corp cannot exceed 100 shareholders.

An S-Corp, however, is still a pass-through entity and will submit an informational return to the IRS known as Form 1120S. Each of the shareholders will be issued a K1. The K1 for each owner will designate how the owner’s share of income, deductions, and credits are allocated for tax purposes on their personal 1040 tax return. To be clear, while an individual is responsible for paying the taxes for a profitable business, the business does not have to physically write the owner a distribution check for the full amount of the company’s profits. In fact, it is advisable that some of the profits be retained by the business to cover future expenses and provide capital for growth.

For my shareholders, I would generally issue a distribution to cover the shareholder’s tax obligations and retain the rest to reinvest in the business. When you are just an investor in an S-Corp, ostensibly you do not work for the business and you do not participate in its management as an officer. You are therefore considered limited in your liability and your income from the business based on your ownership share of the business is usually considered passive income. Passive income, as you will recall, is not subject to FICA or Medicare taxes. Therefore, your income will be subject to federal and state income taxes based on your marginal tax rate only.

NOTE: To be 100% accurate, there are some exceptions where your CPA might designate your income as ordinary income yet not subject the income to self-employment tax since the income is in a corporation. This is especially useful if the company has a loss so it will not suspend in the year of occurrence. However, this situation is beyond the scope of this discussion and is generally a rare occurrence.

Throughout the year, the business may make periodic distributions to compensate you as a shareholder. The business does not withhold taxes on distributions. At tax year-end, the S-Corp would file its Form 1120S showing a net profit after deductions. The S-Corp would issue you a K1 showing your share of the S-Corps income, deductions, and credits. As a shareholder, you will use the K1 from the S-Corp to populate your Schedule E (supplemental income and loss).

When it comes to taxable income, the onus is on you to estimate the taxable income you will receive and then make quarterly deposits to the IRS using Form 1040-ES to cover the anticipated annual tax liabilities. The same is true for your estimated state taxes. To avoid IRS penalties, your tax estimates should add up to at least 90% of your estimated tax liability.

How you get paid depends upon if your an office or a shareholder of an S-Corp. Are you paying people properly as officers and shareholders of an S-Corp?

I would like to acknowledge Karen Absher of KSA Financial & Tax Services for her gracious assistance as a reviewer to make sure that the tax issues conveyed in this post were an accurate representation of US tax law.