Every year, I meet owners who are bright, motivated, and committed to doing what it takes. Many, however, burn out or shut down. Not because their business idea was bad or the market was too small or unreceptive. They struggle because they never learned to see their business as a system.

As a mentor, I can’t count how many times I’ve watched an owner slap a quick fix on a problem in what I call the “band-aid approach.” Sales dip? Run a discount. An employee quits? Hire the next warm body. A supplier misses a shipment? Order extra next time. These quick fixes make them feel like they’re solving problems, but all they’re really doing is playing whack-a-mole. Soon, the same issues resurface, this time just wearing a different disguise.

When I sit down with these owners, my job isn’t to hand them a magic answer. My job is to help them gain a new appreciation of how their business actually runs. Together, we uncover the complex web of interactions that are really driving their results. That’s the heart of systems thinking. And once owners start to see their business this way, it’s like turning on the lights in a dark room. Suddenly, everything about their business makes more sense to them.

There are several ways to map out a business system. To help them visualize the hidden structures that drive outcomes, my three favorite systems thinking tools are:

- Iceberg Model

- Stock and Flow Diagrams

- Causal Loop Diagrams

The Iceberg Model is one of the easiest tools for small business owners to wrap their heads around and to help them change their focus from “what just happened” to “why it keeps happening, so I often start there. However, the two other tools are also very useful lenses to apply systems thinking to your business. If you are unfamiliar with how to create Stock and Flow or Causal Loop Diagrams, I urge you to check them out as well.

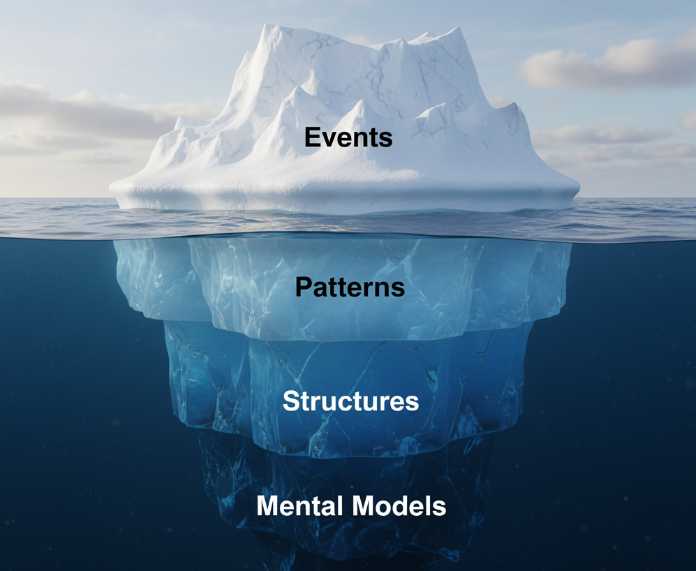

What is The Iceberg Model

The iceberg model is a tool that helps us to see what sits below the surface, not just the visible event. At the top of the model are events. These are the things that happen right in front of you. Just under the surface are patterns and trends. These are the recurring cycles that show up over time. Beneath those are structures. Structures are the systems, agreements, and ways of working that create the patterns and trends. And at the very bottom of the model are the mental models. These are the assumptions and beliefs you or the market hold that quietly shape all the layers above.

If, as a business owner, you only respond to events, you’ll spend your time just patching symptoms. If you notice patterns and trends, you might begin to see what is coming next. But if you’re willing to dig into structures and challenge the mental models at the foundation, you’ll find the highest leverage points to produce lasting change.

Iceberg Model Example

Let me illustrate the concept of the Iceberg model with a somewhat fictional story. It’s built from a composite of several clients I’ve worked with over the past two decades. Meet Troy, a designer of kitchen gadgets.

Troy reached out when his latest gadget wasn’t selling very well. He had built a reputation on designing clever kitchen gadgets, things like a garlic press that doubled as a zester, a jar lid that turned into a cocktail shaker, and a vegetable peeler that would convert into a julienne slicer. All these designs turned heads and went viral online. He sold most of his products directly to consumers through his website and major third-party marketplaces.

Only about 25 percent of his business revenue came from wholesale customers who resold his gadgets to physical retail establishments. However, the volume of wholesale orders was slowly declining, and reorders were happening less often. The slow erosion of his wholesale channel, combined with the flop of his latest product launch, finally pushed Troy to seek help and reach out to me.

Events:

At first, he explained the visible events with his latest product: Sales were falling. Inventory was stacking up, resulting in rising carrying costs. Ads that once worked weren’t converting as they once did, and advertising as a percentage of sales was increasing. Wholesale partners were taking longer to reorder, and orders were for fewer products.

Troy shared his ideas to fix the problems: cut the price, bundle it with his other products, and push harder on Instagram. He was like most small business owners, and his proposed solutions were just reactions to the event at the surface. However, I shared that the events are only the tip of the iceberg, and to resolve the real issues, he would have to dig a little deeper.

Patterns and Trends:

I suggested that before he took any action, he should look back at his previous launches to see if he could spot any patterns or trends.

When we next spoke. Troy shared that the garlic press held its sales momentum for over a year. His next product, the shaker lid, lasted eight months, and the peeler lost much of its momentum after just six months. His latest gadget had collapsed in under two months.

Lined up side by side, the patterns and trends were unmistakable. Each launch peaked lower and died faster. What felt like a one-off disappointment was really part of a downward trend.

Structures:

Once we spotted the patterns and trends, we began to look at the structures shaping them.

Troy’s sales structure leaned almost entirely on direct-to-consumer channels. That was fine when algorithms favored his listings, but he had little control. Paid ads were getting more expensive as more businesses were bidding on the same keywords. Organic reach was getting weaker with Google’s AI Summary. Each launch failed to leverage the momentum from the previous launches, so it felt like each new product was like starting over.

His wholesale structure was also faltering. Even though only a quarter of his sales came from resellers, they were all chasing the same demographic, young home cooks already overwhelmed with nearly identical gadgets, so orders were smaller and reorders were taking longer.

Additionally, his supply chain structure was tied to China. While that kept unit costs low, tariffs, shipping delays, and higher freight costs were cutting into his margins. Worse, when a design change was called for, high minimum order sizes and long lead times made it nearly impossible to adjust quickly.

And then there were the changes to the broader market structure. When Troy started, the kitchen gadget space was smaller, and it was easier to stand out in. Today, the market is much larger and far more crowded with competitors. E-commerce had lowered barriers to entry, and his larger competitors were using automation and AI to design copycat products, scrape reviews for insights, and optimize ads faster than he could.

These weren’t isolated problems. They were the structural realities shaping his results.

Mental Models:

At the bottom of Troy’s iceberg were his mental models, the beliefs that had shaped all his decisions.

He believed a great product sold itself. That had been true once, but not in today’s crowded marketplace. He also believed his audience was fixed, gadget-loving twenty- and thirty-somethings. That belief kept him designing and marketing to an overserved demographic.

He believed cost was the only measure of supply chain health. That belief tied him to overseas production even as tariffs, shipping costs, and slow responsiveness eroded the benefits.

These mental models explained why his structures looked the way they did. And until he was willing to challenge them, his patterns and his disappointing events would keep repeating.

The Breakthrough

The iceberg model works because once you can see these deeper layers, the leverage points become clearer, so you can make the necessary changes.

For Troy, the breakthrough came when he realized he didn’t have to keep competing in the same saturated market. The gadget space was not only larger now, but it was also more crowded. He needed to rethink who he was designing for.

That’s when we identified an overlooked market: seniors.

Older consumers were buying online more than ever. Many had disposable income. Many wanted to keep cooking and living independently, but struggled with grip strength, dexterity, or eyesight. Most kitchen gadgets ignored them. Handles were too small, the packaging text was hard to read, and cleaning was frustrating.

Troy’s new mental model became: “A great product is one designed for the right customer, not just for cleverness.”

Working Back Up the Iceberg

That shift in belief reshaped his structures.

He redesigned gadgets with larger, more comfortable handles. He added simple cleaning brushes. Packaging used clearer and larger fonts. Product descriptions highlighted safety and ease of use.

He also shifted his marketing. Instead of relying only on influencers who appealed to young cooks, he began targeting seniors and caregivers, positioning his gadgets as tools that made everyday cooking easier and more enjoyable.

He diversified his supply chain, too. Some production stayed in China, but he sourced regionally as well. That gave him more flexibility and reduced the risks from tariffs and shipping delays.

The patterns began to change. Instead of a big spike and a fast collapse, sales grew more steadily in a less crowded market. Reviews praised usability and thoughtful design. Senior-focused wholesalers reordered more quickly and in larger quantities.

Why the Iceberg Model Matters

Troy’s story is fictional, but the lessons are real. I’ve worked with thousands of business owners over the past twenty-plus years, and the same trap shows up again and again. Business owners focus only on what they can see. They throw tactics at events. Sometimes they may spot the patterns and trends, but until they examine their structures and mental models, they rarely fix the root causes.

The iceberg model helps business owners ask better questions, stop chasing symptoms, and design systems that produce the outcomes you actually want.

Questions to ask as you work down the iceberg

The real power of the iceberg model is that it gives you a practical way to challenge your thinking. Instead of reacting only to surface events, you can use it to guide a structured set of questions that lead you deeper into the root causes of your business challenges. The following are some examples of the types of questions you can use to help you dig deeper.

Events (the visible tip):

- What exactly happened, and how is it showing up in my business right now?

- Who was affected: customers, employees, or partners, and in what way?

- What immediate steps have I already taken, and did they solve the problem or just mask it?

Patterns (just below the surface):

- Has this happened before, and how often does it repeat?

- Do I see any seasonal, cyclical, or outside triggers that line up with these results?

- Is the overall trend improving, declining, or holding steady?

Structures (the system that produces the patterns):

- What processes, agreements, or supply chain choices are locking this pattern in place?

- Are incentives or contracts pushing behavior that works against me?

- If I changed one part of the system, what ripple effects would it create across the business?

Mental models (the deepest layer):

- What beliefs or assumptions led me to build my structures this way?

- Are those beliefs still true in today’s market, or are they outdated?

- Which one assumption, if I challenged it, could open up the most new opportunities?

When you’re willing to ask those questions, you’ll start to see beneath the surface. And once you see, you can change what matters most.

How can you apply the iceberg model to your own business challenge?