We are all prone to overestimating our abilities from time to time, but when it comes to starting a small business, the effects can be devastating. The Dunning-Kruger effect, as it relates to entrepreneurship, is a cognitive bias of overconfidence exhibited by the founder. The founder’s overconfidence is based on their unrealistic expectation that they know far more about the industry and business than they actually do.

After nearly two decades of mentoring startups, I believe that the Dunning-Kruger effect alone is responsible for many small businesses failing in their very first year.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that was coined in 1999 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger, who were Cornell psychologists. Their findings were published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, in a paper called “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.”

As a result of the Dunning-Kruger effect, founders of small businesses tend to overrate themselves and underrate more experienced people. Many founders are full of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories about how business works, facts, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that, unfortunately, look like useful and accurate knowledge, but are completely unhinged from reality.

“In many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge”

David Dunning.

Failure to Understand an Industry

Many of the clients that I see are non-industry insiders that have observed a market failure and have come up with a plan to address it. If you look at some of the most spectacular startup failures in history, you will see the same pattern. WeWork founder Adam Neumann created a clothing company and thought he could start a commercial real estate business catering to businesspeople that needed flexible office space. Greg McLemore, the founder of Pets.com, had a children’s toy company and thought selling pet supplies was the same as selling toys. In nearly all cases, the founders thought their knowledge of one industry could simply be applied to another industry.

Many of my clients are looking to start a business in an industry that is new to them. They perform basic opportunity validation by talking to people in their personal network, who, on the other hand, are often reluctant to disagree with their friend’s observations in order to preserve their friendship and mistakenly conclude that these non-industry insiders all agree with their solution, which must therefore make sense. Emboldened by the confirmation of their idea, they dive headlong into the process of trying to design a business around their solution.

While it is an extremely exciting time for these founders who frequently exude confidence, I’m always extremely cautious to encourage their business idea at this stage because most often, it is a recipe for disaster. Often, when I challenge one of their assumptions, these overconfident founders snap back saying that I simply do not understand.

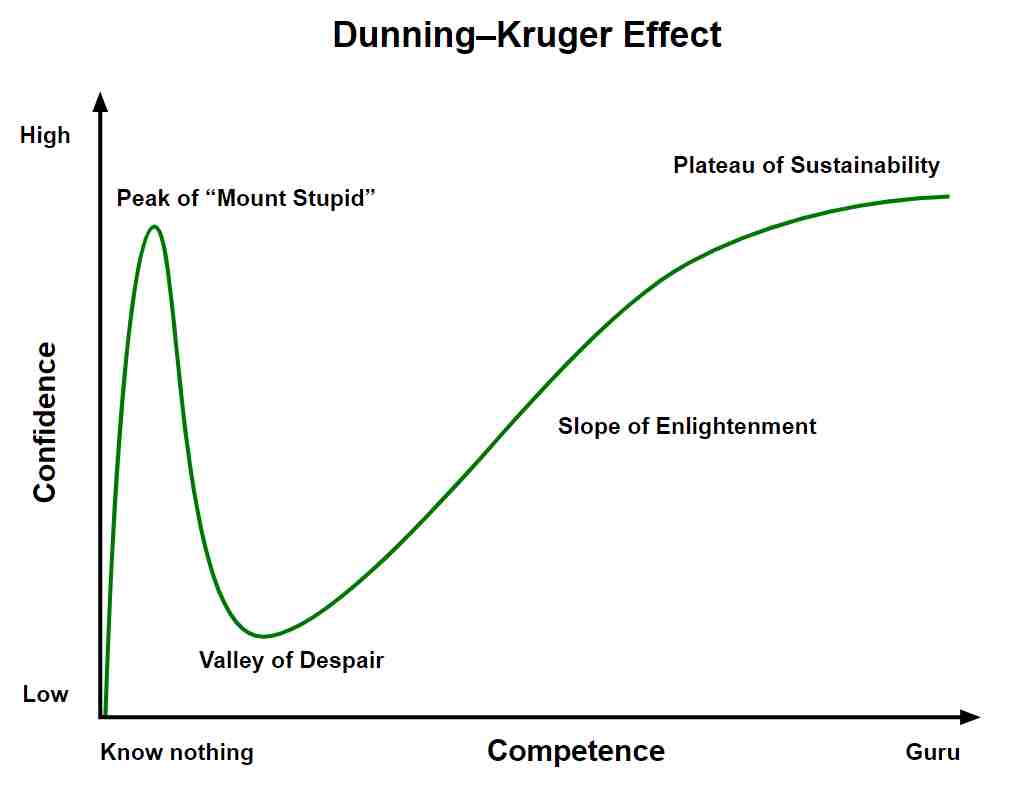

Being industry outsiders, they are ignorant of the market forces that face the industry. Much later, after they have deployed serious resources in the form of money and time, they begin to see the issues with their idea that prevented industry insiders from acting on a similar idea. Eventually, many of these founders slip into the “Valley of Despair”. However, some founders remain on “Mount Stupid” in denial until ultimately, they become exhausted and broke.

Another common client I frequently encounter who suffers from the Dunning-Kruger effect is one who is looking for a self-employment opportunity. Their primary desire is just to no longer work for the man. Often, they have read someone’s book or taken a course and buy into the idea that they can simply copy the author’s success formula and achieve the same level of success. Unfortunately, they will never know everything the author did to achieve their success and the applicability of the formula seldom works the same for them in another industry since they lack the author’s skills and knowledge.

Because I own commercial and residential real estate to produce passive income, many of my clients discover my profile and ask me to be their mentor to help them do the same. While they know little to nothing about the real estate industry, they think they will have success with their first deal. I have spent almost two decades doing everything from fix and flips, model home leasebacks, lease-to-own deals, building spec homes, etc. During that time, I developed a deep network of trusted service providers and advisors. I accumulated numerous lessons along the way, many of them from failures that I could afford since I used mostly my own money to fund my real estate education. Reading a book or getting a few hours of mentoring from me will not come close to providing all the lessons I learned in nearly two decades working in the real estate industry.

All these clients represent the essence of the Dunning-Kruger effect in that they are neither experts in the industry they seek to enter, nor even target users of their solution. However, they falsely believe they have the skills and knowledge to succeed. As a result, they overestimate their knowledge and their ability to execute their idea until failure ensues.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect in Startups

When an entrepreneur decides to start their own business, the path forward appears initially easy and clear. The founder truly believes that they know the market and have foreseen all the risks and problems and they are full of confidence. A founder’s positivity bias tends to cause them to see only positive examples of individual entrepreneurship. At this point, the adrenaline and emotions run high as the future looks very promising and success is almost assured as they are at the top of the Dunning-Kruger curve.

Confidence that your venture will succeed is one thing, but overconfidence can cause serious problems for not only the founder but others as well. Relationships and careers can be ruined as the founder becomes an evangelist of their own business idea. This is especially true of charismatic leaders that have had some previous successes. Their energy and over-optimism can convince other people to quit their full-time jobs, work for free in exchange for a piece of the business or invest money in their reckless idea.

While some founders will never leave “Mount Stupid” or accept any form of rational criticism of their idea, many will eventually recognize the illusions they have mistaken for knowledge. After reality hits the founder, they quickly lose confidence as they descend into the “Valley of Despair”. At this turn of confidence, a lot of startups simply fail and never get back on track. For small businesses, this generally happens in the first year.

When the founder is at the bottom of the Dunning-Kruger curve and remains committed, the awakening and enlightenment come. The successful founder realizes their own incompetence and seeks to overcome it.

Dunning-Kruger and Investors

Sometimes, a business gets funded by an angel investor. While angel investors are often what I call smart money since they bring more than money to the business such as network contacts, angel investors are often just as susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect as founders, as they chase the next unicorn.

Angel investors often accumulate their net worth after having a successful exit with a previous business. Many feel they have the Midas Touch and can do it again in a new industry. However, previous success in a different industry is no guarantee of success.

Although I had two successful multi-million dollar business exits, they were both in the industry (documentation and training) in which I had worked for over a decade prior to founding the companies, and both included many of the same team of managers and employees. When I ventured outside the industry with new people, similar success proved more elusive.

Dunning-Kruger and Freelancers

Historically, most successful enterprises were started by entrepreneurs between the ages of 45 and 55. They brought industry experience, business skills, connections, and access to capital accumulated over decades of being in the trenches. However, after the pandemic, there was a marked surge in entrepreneurship by many young adults, many fresh out of college with limited or no industry or real work experience. According to a study done by Randstad, 51% of respondents between the ages of 25 and 34 are considering leaving their current jobs to start their own business.

It pains me to know that many of these young enthusiastic entrepreneurs will also fail because of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Many will embark on a freelance career that requires minimal financial investment. A large financial commitment often brings additional scrutiny to the business idea. While I have never been a big fan of debt financing for a startup, it does force people to write a business plan which helps the individual realize that they didn’t know what they didn’t know. At the very least, the process of developing a business plan and pitching it to a lender or investor leads to the entrepreneur’s assumptions being challenged.

While most freelancers have an abundance of technical knowledge, they frequently lack the business acumen and network contacts necessary to succeed. This is especially true with younger freelancers. Their overconfidence in their ability to operate their freelancing career as a profitable business causes many freelancers to barely make a living until they give up freelancing and accept a job working for “The Man, or “The Woman”.

In my experience, working with literally thousands of freelancers, the most successful ones are middle-aged or older individuals that worked in an industry for many years, then either quit or retired and sell their expertise to their former employer on an hourly basis.

Dunning-Kruger and Hiring

One more outcome of being on the top of “Mount Stupid” in the Dunning-Kruger curve is the inability of the founder to identify other people’s abilities and knowledge accurately. Founders on “Mount Stupid” do not accept the fact that anyone else can know something better or have a clearer picture of the industry or business than themselves. As a result, they fail to hire strong people who could challenge their worldview or provide constructive feedback.

The Solution to Overcome the Dunning-Kruger effect

As I think I’ve made abundantly clear, one way to avoid the Dunning-Kruger effect from rearing its ugly head is to start a business where you already have the industry knowledge and lots of network contacts.

Since most founders have minimal business acumen, I recommend they create a relationship with a mentor that not only knows their business but also knows their industry. Find a mentor that has been there and done that. A good mentor who has direct business experience will be able to teach you things beyond your personal experience. Your mentor will have lived through economic conditions and business situations that you have yet to cross. As long as you have an open and honest relationship with your mentor, they will be able to point out areas where you may have misconceptions or even be outright wrong. Your responsibility is to be open to the possibility, and even the likelihood, that some of your ideas may be way off base.

Finally, try not to take any money from an outside source until you have proven your business model. Bootstrap your business during the idea validation and proof of concept stage. Once you get an investor or a lender on board, you will tend to focus too much on the positive message and become less receptive to feedback that could tarnish your standing with an investor or lender. You will be forced to project a level of confidence to maintain these relationships that you have yet to earn.

How will you use your knowledge of the Dunning-Kruger effect to avoid premature failure of your startup?

Keyword: Dunning-Kruger effect