Prospect theory assumes that the likelihood of a loss of money or opportunity and similar potential gains are valued differently, which has some direct implications for small business marketing.

Prospect theory is a subset of a larger psychological discipline known as behavioral economics. The term prospect theory was originally coined as part of a series of studies performed by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman and is summarized in the book Thinking Fast and Slow. Much of the work performed by Tversky and Kahneman focuses on understanding the two brain systems.

System-1 is the reactive and automatic or fast thinking part of the human brain. System-1 develops causal association, suppresses ambiguity, and constructs stories that are as coherent as possible.

System-2 is the logical and thoughtful, but resource-intensive and slow thinking part of the brain. System-2 is capable of doubt since it can maintain incompatible possibilities, but maintaining doubt takes more energy so it wants to slide into certainly and often defaults to agreeing with System-1.

Creating marketing content, that appeals to System-1 using prospect theory, utilizes the consumer’s own biases to drive higher sales conversions.

At the core of prospect theory is the concept that individuals place greater value on wins or gains and are more open to risk-taking to avoid losses. By simply framing your value proposition through the lens of prospect theory, you can tap into a consumer’s System-1 brain.

3 Operating Characteristics of Prospect Theory

There are three operating characteristics or principles that contribute to prospect theory.

Neutral Reference Point

According to Kahneman, a person’s neutral reference point can be explained by a simple experiment. Imagine that you had 3 bowls of water. One bowl filled with ice and cold, one bowl at room temperature, and a third bowl filled with very warm water.

If you place one hand in the very warm bowl and the other in the cold bowl for about one minute and then place them both in the room temperature bowl, each hand will have a different sensation. The hand that was in the cold bowl will perceive the room temperature bowl as feeling warm. The opposite would be true for the other hand, which will perceive the room temperature bowl of water as feeling cool.

The neutral reference point represents the status quo which was established by leaving your hand in the cold or warm water. While the room temperature bowl was the same for both hands, the neutral reference points were different.

When it comes to the neutral reference point in prospect theory, it is the specific conditions that exist for a prospect before an alternative is presented.

Principle of Diminishing Sensitivity

The principle of diminishing sensitivity states that low probability outcomes are typically overweighted during decision-making.

This overweighting of wins is what drives entrepreneurs to start new businesses even though the odds of success are against them, and why people buy lottery tickets even though the odds of winning are not in their favor.

In contrast, the overweighting of losses is what explains why many business owners load up with all kinds of business insurance. While the odds of a natural disaster such as a fire or flood wiping out an owner’s small business are very rare, many businesses act like scared rabbits and buy business insurance to prevent losses, just in case.

The principle of diminishing sensitivity also explains how Relative Price Psychology causes many people to drive an extra 20 minutes to save $7.00 on a copy of TurboTax that sells for just $40, and not willing to drive an extra 20 minutes to save the same $7.00 on a 27-inch computer monitor that sells for $270.

Principle of Loss Aversion

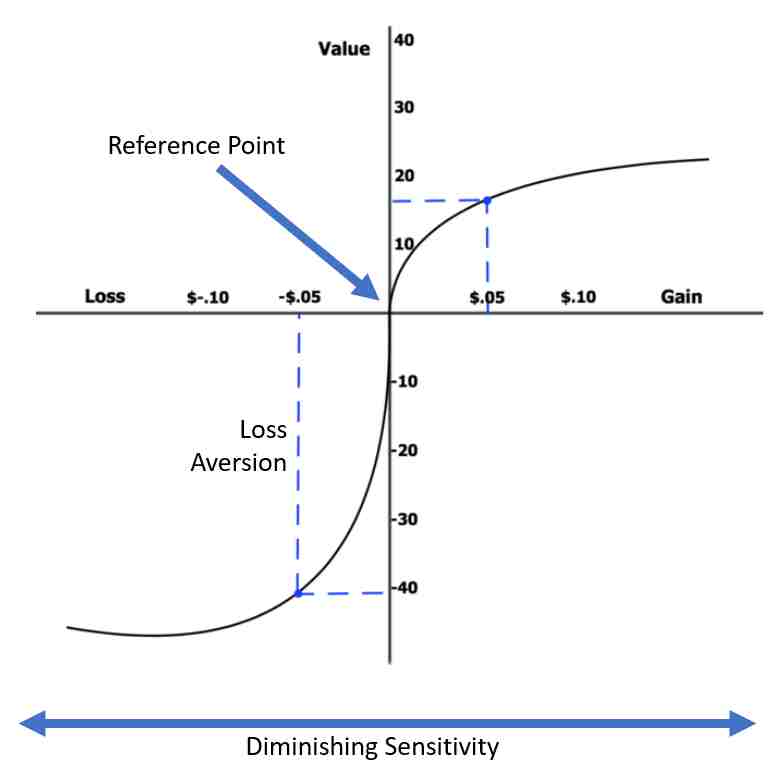

The principle of loss aversion is the tendency to prefer to avoid losses rather than acquiring equivalent gains.

Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that describes why the pain of losing is psychologically much more powerful than the pleasure of gaining. The loss felt from losing money, or anything else of value can feel worse than the gain of that same thing. Simply put, it’s better not to lose $20, than to find $20. In fact, loss aversion gets stronger as the stakes of a gamble or choice grow larger.

Kahneman is quoted as saying: “The response to losses is more extreme than the response to gains.” And “Losses loom larger than gains” meaning that people by nature are averse to losses.

Prospect Theory and Framing

There are two frames that small businesses can use to tap into what Kahneman describes as the System-1 cognitive biases that shape prospect theory:

- Potential for Gains

- Potential for Losses

The basis of prospect theory can be explained by a simple game of coin flip. The probability of a coin landing heads or tails is statistically 50/50. However, the frame of the coin flip colors a person’s risk tolerance and therefore their decision-making process.

The Gain Frame

If you were given two options, which one would you choose?

Option #1: you receive $100. There is no risk, and you would simply get the cash. By accepting option #1, you are guaranteed to walk away $100 richer.

Option #2: we flip a coin. If the coin comes up heads, you will receive $200 or twice as much as option #1. However, if the coin lands on tails, you get $0.

Which did you choose?

Statistically, with option #2, your odds are 50/50 that the coin will land on heads. If you played the game over and over again, statistically you would walk away with an average of $100 per coin flip just as in option #1.

Rationally, the options are equal, but when Tversky and Kahneman ran this test with real people, test participants overwhelmingly chose option #1. The certainty of a gain had a greater impact on a person’s decision-making. Even though the person could have doubled their money when it comes to gains, the certainty effect prevails more than twice as many times.

But what if the experiment was flipped?

The Loss Frame

The experiment was repeated this time in terms of certainty of loss.

Option #1: you will have to pay $100. There is no risk of losing more money, you would simply have to pay $100 in cash. By accepting option #1, you will walk away $100 poorer, guaranteed.

Option #2: we flip a coin. If it comes up heads, you will have to pay $200 or twice as much as option #1. However, if the coin lands on tails, you owe nothing.

Which did you choose?

Statistically, with option#2, your odds are 50/50 that the coin will land on tails. If you played the game over and over again, you would average losing $100 per coin flip just as in option #1.

Rationally, the options are equal, but when Tversky and Kahneman ran this test with real people, test participants overwhelmingly choose option #2. Test subjects were more willing to gamble on a coin flip and risk twice as much to avoid a loss. When it comes to losses, people are more than twice as likely to risk a greater loss than to accept a certain loss.

The two experiments demonstrate that the displeasure associated with losing a sum of money is generally greater than the pleasure associated with winning the same amount. Versions of this test have been repeated over and over with the same outcomes and are proof that people are more willing to accept the certainty of a gain and not risk losing one, but are predisposed to gamble to avoid losses.

So, how does this translate to marketing?

Prospect Theory Frames and Marketing

When options are framed in terms of gains, a prospect’s tolerance of risk decreases, and they prefer the option of a sure win. However, when options are framed in terms of losses, the prospect’s tolerance of risk increases.

For years, marketing has been based on what is known as the Utility Theory which states that when a person is faced with uncertain outcomes, rational people weigh the potential gains and losses to maximize utility. Prospect theory has debunked much of the utility theory and shows that utility pales in comparison to instinct and emotion, which are the drivers of the cognitive biases that prospect theory describes.

Prospect theory maintains that decision-making is affected by emotion and is reflected in the framing of the alternatives. The concept of utility can’t account for the results of the coin flip experiment described above, in which numerically identical options were assessed in fundamentally different terms. Clearly, the human mind is not only sensitive to logic when evaluating gains and losses, prospect theory exposes these cognitive biases when it comes to decision-making.

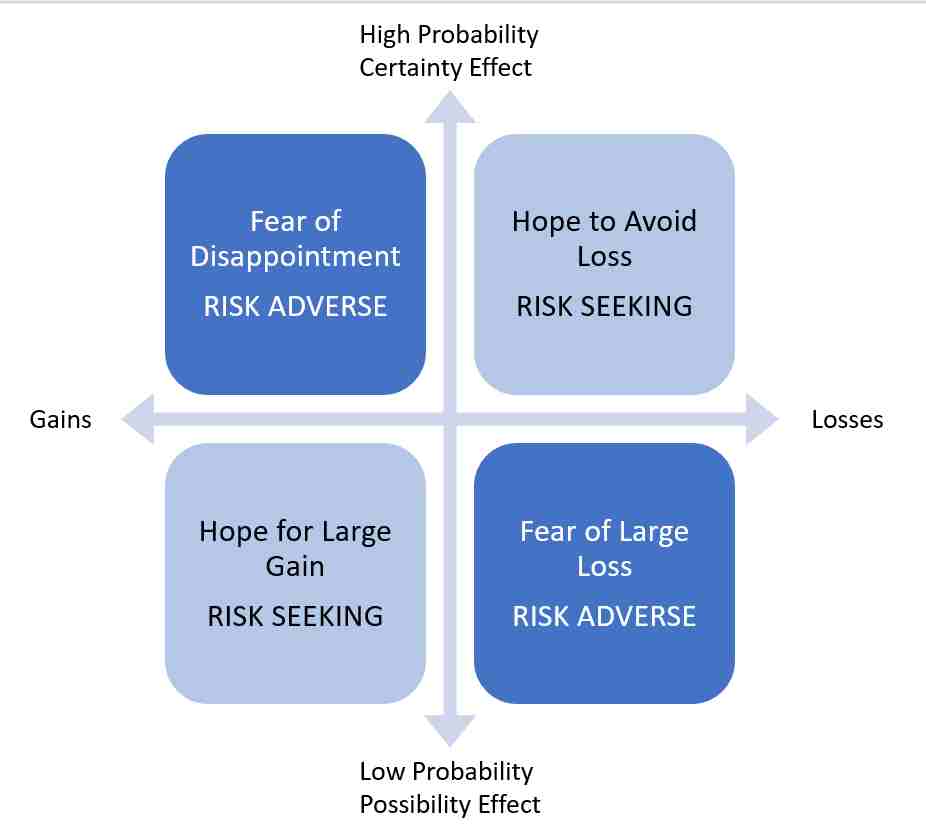

However, the potential of gains and losses is modified by two other effects:

- Certainty Effect – High Probability Outcomes

- Possibility Effect – Low Probability Outcomes

The Certainty Effect

The certainty effect happens when people overweight outcomes that are considered certain, as opposed to outcomes that are merely possible. The certainty effect leads individuals to avoid risk when there is a prospect of a sure gain. It also contributes to individuals seeking risk, up to a point, when one of their options is a sure loss, as described above.

So, what does this mean for the business owner?

Gain Frame with High Probability Outcomes

In situations where a prospect faces a high probability of gain, studies have shown that prospects have a greater tendency to be risk-averse and are predisposed to take more guaranteed gains because they are motivated by the fear of disappointment or loss aversion associated with greater risk-taking. To take advantage of this cognitive bias, a business should sell the certainty of outcome.

For example, a business could offer a satisfaction guarantee. When you offer a 100% money-back guarantee, you have removed all risk and made the person’s purchase safe in that if the product fails to perform as advertised, they get their money back. Businesses could offer a settlement to an unhappy customer or vendor where the certainty of the amount offered is clear vs taking the case to court where the damages could be higher but the amount less certain.

Loss Frame with High Probability Outcomes

In situations where a person faces a high probability of loss, studies have shown that business owners have a greater tendency to be risk-seeking and more willing to gamble because they are motivated by the hope of avoiding losses. To control this cognitive bias, a business should acknowledge the risk of the probable outcome.

Unfortunately, loss aversion when it comes to high probability outcomes is a slippery slope that all business owners should acknowledge.

“People who face very bad options take desperate gambles, accepting a high probability of making things worse in exchange for a small hope of avoiding a large loss. Risk-taking of this kind often turns manageable failures into disasters. The thought of accepting the large sure loss is too painful, and the hope of complete relief too enticing, to make the sensible decision that it is time to cut one’s losses. This is where businesses, that are losing ground to superior technology, waste their remaining assets in futile attempts to catch up. Because defeat is so difficult to accept, the losing side in wars often fights long past the point at which the victory of the other side is certain and only a matter of time.”

Daniel Kahneman

Investors in stocks tend to hold on too long to stocks that have dropped in value in the hope that the stock price will rebound because accepting the emotional blow of the loss is just too difficult.

In business, when there is a high probability that the business will not succeed, yet there remains a small chance that it will survive, a logical person would look at the odds, accept the nearly inevitable outcome and focus on preserving whatever cash is left. However, according to Tversky and Kahneman’s research, this is rarely the case, since most people would stay the course despite the small probability of success, to avoid the inevitability of a loss, which brings us the then next effect.

Possibility Effect

The possibility effect happens when people overweight outcomes that are possible but not probable and overestimate their chances of occurring.

So, what does this mean for the business owner?

Gain Frame with Low Probability Outcomes

In situations where a person is faced with a low probability gain, studies have shown that prospects have a greater tendency to be risk-seeking and are motivated by the hope of a large gain.

To take advantage of this cognitive bias, businesses should sell the dream. For example, we see many businesses that describe the high-income potential that their product or service might provide the entrepreneur, even if few people actually make enough money from it to cover their cost. Or when pitching to an investor, the business should sell the future and how their solution will achieve market share and deliver a high rate of return on their investment.

The propensity of people to focus on the upside explains why so many people start businesses even though they know that the possibility of success is stacked against them. This also explains why many investors invest in startups even though most will fail.

“When the top prize is very large, ticket buyers appear indifferent to the fact that their chance of winning is minuscule. A lottery ticket is the ultimate example of the possibility effect. Without a ticket, you cannot win, with a ticket, you have a chance, and whether the chance is tiny or merely small matters little. Of course, what people acquire with a ticket is more than a chance to win; it is the right to dream pleasantly of winning.”

Daniel Kahneman

Loss Frame with Low Probability Outcomes

In situations where a person may face a low probability loss, studies have shown that prospects have a greater tendency to be risk-averse and are motivated by the fear of a large loss.

To take advantage of this cognitive bias, businesses should sell peace of mind. The business could offer the customer an extended warranty or insurance policy for an additional fee. The possibility effect when it comes to low probability outcomes says that many people are willing to pay a premium to reduce or eliminate the risk of a loss. This is why many businesses offer extended warranties and people continue to buy them, even though most extended warranties are a rip-off.

“People are willing to pay much more for insurance than the expected value, which is how insurance companies cover their costs and make their profits. Here again, people buy more than protection against an unlikely disaster; they eliminate a worry and purchase peace of mind.”

Daniel Kahneman

How can your business use prospect theory to frame its marketing content around potential gains and losses and leverage the prospects system-1 cognitive bias to improve sales conversions?