Good habits allow you to do more with less mental effort, while bad habits create problems you will eventually need to deal with later. When it comes to business, wouldn’t it be nice if we could cultivate more good habits around business activities and free ourselves from many self-defeating bad habits that lead to long-term problems? Well, according to James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits, you can. It all starts with an understanding of how our addictions create habits.

As humans, we all have an addiction. We are addicted to dopamine. Dopamine plays an integral role in our reward system. Dopamine is a group of brain processes that control our motivation, desire, and cravings. Higher dopamine levels create feelings of euphoria, bliss, and enhanced motivation and concentration. Without it, humans are prone to mental illness, including depression. Exposure to substances and activities that increase dopamine creates addictions, and addictions are basically habits by another name.

But what is a habit? A habit is defined as a routine or regular behavior that gets harder to give up the longer that behavior goes on. A common example of a habit can be seen in how people start their day. Most people have a particular morning ritual consisting of various habits.

My morning ritual begins with making coffee, after which I take Luger, my German Shepherd, out into the back forty to pee. Returning to the house, I grab my cup of coffee, head to my recliner, prop up my feet, grab my iPad and read the news and business articles while Luger curls up next to me. I have this same routine every day, and I look forward to it every morning. I guess that you also have a sequence of behaviors that you consistently do each morning.

When a habit generates a good result, we should want more of it. Working out daily is a good habit that will improve your health and produce good health results. When a habit generates a bad result, we should want less of them. Smoking is a bad habit that will eventually lead to health issues.

Habits are Unconscious

Habits are behaviors that are relegated to the subconscious mind. We do them without conscious thought.

Have you ever heard the saying, “We only use about 10% of our brain?” I think this idea is based on the fact that about 10% of our brain represents the conscious part, while the other 90% is the subconscious part, which is what we do without really thinking about it.

The most obvious example for me of a subconscious habit is driving. I always listen to a nonfiction audiobook while I’m driving alone. My conscious mind is focused on the narrative of the audiobook and how the message might create meaning for me. My unconscious mind controls the activities associated with driving. I think you will all agree with the experience of getting to a destination, thinking, “Wow, how did I get here” and having no real recollection of the drive.

However, when you first learned to drive, maintaining your speed, keeping the vehicle between the lines, and checking your mirrors for other traffic were all conscious efforts. They became a habit that no longer required conscious attention to the tasks associated with driving. Your brain was freed up so you could do more with the drive time, such as listing to an audiobook as I do, because driving became a habit relegated to the unconscious mind. The act of driving became automatic, so your conscious mind was freed up to take on other tasks.

This incredible human adaptation can be mastered for good; however, few people really use it effectively to cultivate more good habits and reduce bad ones.

We want to make a good process a habit by moving it from the conscious to the unconscious mind so we can stop paying attention to it and just do it over and over without thinking.

Harness Dopamine to Create Habits

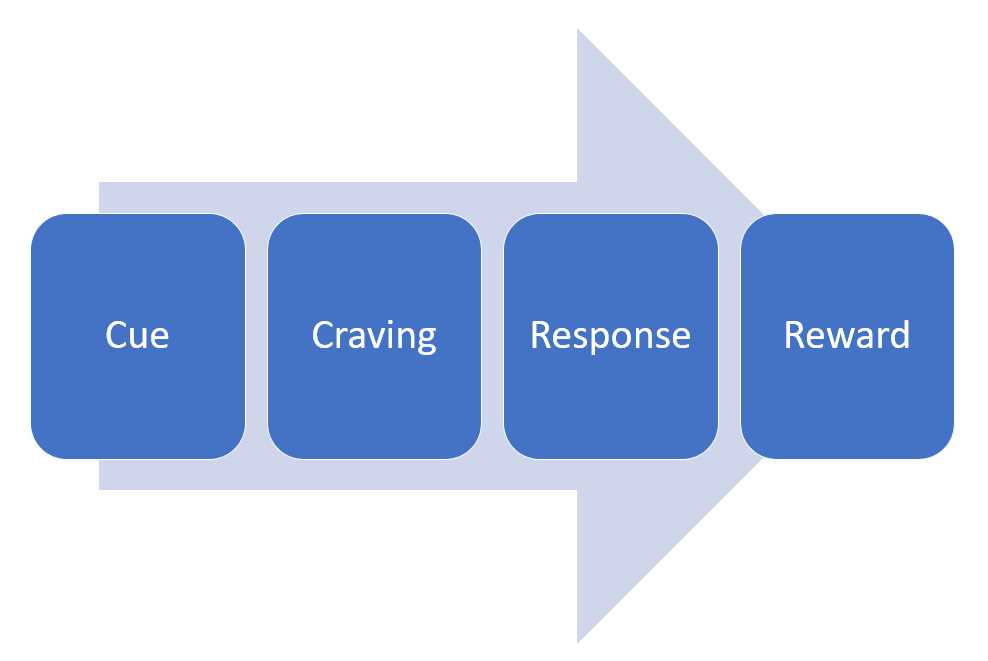

James defined four laws of behavior change and a simple set of rules anyone can use to create good habits and reduce bad ones. When it comes to behavior change, there are four steps beginning with a “Cue” followed by a “Craving,” which leads to a “Response,” which ultimately ends with a “Reward,” which is that shot of dopamine.

The four laws of building good habits to change behaviors, according to James, are to make them:

- Obvious and Visible (Cue)

- Attractive (Craving)

- Easy (Response)

- Satisfying (Reward)

As you sit down to watch your favorite TV show, imagine seeing an ad for some tempting snack food. That is the Cue, and it is obvious and visible. The thought of a snack leads to a desire for a snack as you settle in to watch TV. This is the Craving, and it is attractive. You decide to get off the couch and go to the pantry to see what looks good. This is the Response, and it is easy because the pantry is close, and it is not like you had to go to the store. You select a tasty snack from the pantry. As you eat it, your reward is the satisfying shot of dopamine you receive.

Each day that ad runs at about the same time, eliciting the same response from you to grab a snack. Eventually, you no longer need the ad to start the process. Grabbing a snack from the pantry out of habit before you sit down to watch your favorite TV show becomes part of your evening routine, without the Cue from the ad.

To break bad habits, we simply invert the four rules to make them:

- Invisible (Cue)

- Unattractive (Craving)

- Difficult (Response)

- Unsatisfying (Reward)

Dealing with Cues (Visible/Invisible)

The cues that spark existing habits are often invisible to you because they already exist in the subconscious and are automatically based on cues you fail to recognize consciously. Since our response to these cues is hardwired into our unconscious, the first step to any behavior change is “awareness.”

James says that to create a new habit, you need to create an “Implementation Intention Formula.” He provides an example of the formula:

I will [behavior] at [time] at [location].

So, for example, you might create the following implementation intention formula to avoid distractions:

“I will [turn off my phone notifications] at [9:00 am each morning] when I’m at [the office].”

James goes on to explain how habit stacking can improve your ability to create sustainable change. In the example above, let’s assume that you have already established a habit of drinking coffee every morning when you arrive at work while you check your email. You might link an existing habit with a new one by saying,

“After I drink my coffee and have checked my emails…I will [turn off my phone notifications] at [9:00 am each morning] when I’m at [the office].

So after [current habit], I will [new habit].

Dealing with Cravings (Attractive/Unattractive)

Dopamine is not only released with the experience. It can also be released with the anticipation of pleasure. In the earlier snack example, it was the craving that released a quick shot of dopamine that got us to move to our response action. To take advantage of this, you can do what James calls Temptation Bundling. I discussed a form of temptation bundling in the post on commitment devices. For example, if you do not like making cold calls, bundle the period of cold calls with something you like, such as drinking that Chocolate Crunch Frappuccino you love. No cold calling, no Frappuccino.

One thing that James points out is that many habits are not intentionally created. I have often heard that you are the average of the five closest people you associate with regularly. Therefore, many habits are not deliberately created but are imitations of the habits of the people you associate with frequently. Most people started smoking not by deliberately choosing to smoke but because they adopted the habit from their friends.

If you want to adopt a new habit or behavior, join a culture that models that behavior. Therefore, if you want to be a better entrepreneur, join something like a mastermind group of entrepreneurs with the kind of habits you want. Over time, you’ll begin to imitate many of their habits.

Another tactic James postulates has to do with neurohacking using the power of language. He suggests replacing the word “have” with “get.”

If you have a fear of speaking in public, change

“I have to teach a class.” to

“I get to teach a class.”

While it is a subtle nuance, it can make all the difference because it is a mindset change. The power of the language you use can turn your fear of public speaking into excitement about speaking in public. Your heart may still be racing when you get up to speak, but it is not out of fear but excitement.

Dealing with Responses (Easy/Hard)

Habits are not created by time but by the frequency and number of repetitions that will create a habit. Over time, it gets easier and easier to adopt a new habit. Rather than using brute force to change a behavior, it is better to make the habit easy to repeat and effortless. So, what you want is to reduce the friction of good habits and increase the friction to discontinue bad ones.

Unless you are an accountant, nobody likes tax season. For most of us business owners, properly recording all our revenue and expenses in order to have the data we need to file our annual income taxes is a chore. To reduce the friction of annual tax accounting, record your revenue and expenses as they occur rather than saving them all for April. Leaving the bulk of the work to the last minute creates too much friction, and you will continue to dread tax season and avoid doing your accounting.

To eliminate bad behaviors, make them more difficult rather than easy. If you are prone to distractions by checking text messages throughout the day, place your phone in another room to make it more difficult to check those texts.

When my wife Kim wanted to give up smoking, she decided to add some friction to her smoking experience by forcing herself to go outside whenever she wanted to light up a cigarette. When it was cold or snowy in the winter, she thought long and hard about having a smoke.

Dealing with Rewards (Satisfying/Unsatusfying)

Anything satisfying will keep you coming back. What is rewarded is repeated, and what is punished is avoided. This is known as Operant Conditioning. The unfortunate thing about business is that there is almost always a delayed return. Since there is no immediate gratification, we tend, as humans, to exhibit Time Inconsistency which is a fancy way of saying we value the present more than the future. A potential large reward in the future holds less weight than a small but certain reward in the present.

The problem is that with bad habits, there is often instant gratification and a long-term problem. However, with good habits, the reward will happen in the future, but the reward is often much greater. So how can you overcome this time inconsistency problem? Add a little instant gratification when you establish a new good habit that will pay off more in the long term. Conversely, add a little pain to bad habits you want to break.

Perhaps you reward yourself with a cocktail on the evening of the day you brought your business accounting up to date. Or you deny yourself the opportunity to watch the game because you failed to keep your emotions in check and yelled a profanity at an employee.

Incentives help to start a new habit, but over time, through repetition and frequency, the habit becomes part of your self-identity, and the incentives can be phased out as your identity alone will sustain the habit going forward.

Take it Slow

James makes it clear that you must establish a new habit before making it better. He states that if you try to perfect a habit from the start, you often overdo it and burn out. If you expect too much from yourself, it will feel like a chore. There is a delicate balance between doing too little and reaching the point where it feels more like work. The key is to make the habit you are trying to adopt enough to move the needle but not enough to make it feel like a chore. You can always do habit stacking to make it better once you have established a new base habit.

What new good habits will you start, and which bad ones will you phase out?