What separates good companies from great ones? According to Jim Collins, the author of Good to Great, one factor is what he calls the Hedgehog Concept. So, what is the hedgehog concept? In the research Jim Collins and his team performed when writing the book, they looked for a pattern – the one big thing – those great companies all had in common.

They sought to find one big thing that would explain a company’s greatness compared to their competitors. They looked at good companies that bounced along for years in the middle of the pack in their industries and then experienced an inflection point that caused them to consistently pull ahead of their peers for more than a decade. When they laid out all the data they gathered, what they found was an underlying framework that each of these breakthrough companies had in common.

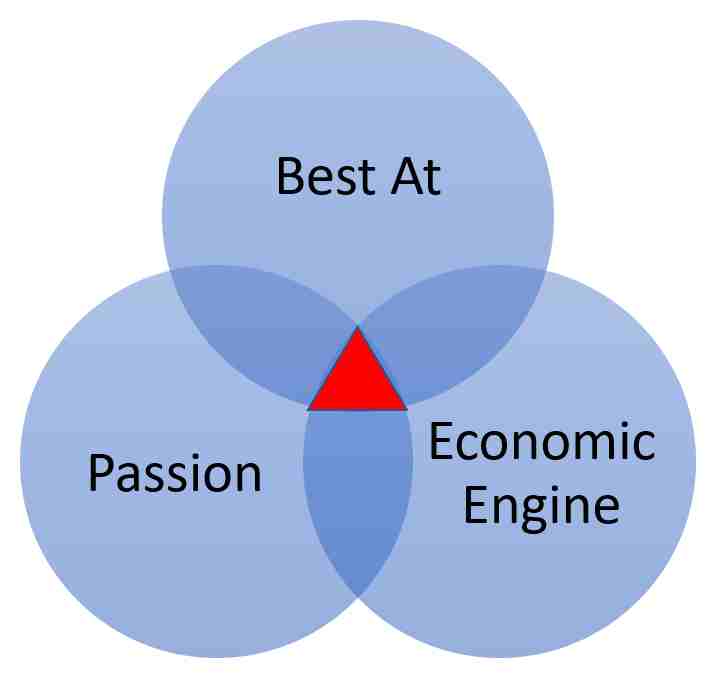

Each of the companies that transitioned from good companies to great ones had developed a deep understanding of three facets. Jim and his team organized these facets into a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles, then translated these understandings into a simple concept and the hedgehog concept was born.

Why is it called the Hedgehog Concept?

The hedgehog concept is based on an ancient Greek parable that states;

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows but one big thing.”

Greek parable

When I think about the hedgehog concept, it reminds me of that scene in City Slickers where Curly, played by Jack Palance, shares his secret of life with Mitch (Billy Crystal) – “one thing”.

Foxes are known to be clever and sly animals. They sit near the top of the food chain and are known to be able to escape just about any tricky situation. Foxes are patient and persevering when it comes to picking apart a problem until they can solve it. But foxes have too many different strategies they use to get what they want. Rather than having one big thing, an attribute that works really well and is better than any other predator, they have a wide range of skills and attributes. None of their skills and attributes are optimal adaptations compared to all other animals.

Hedgehogs on the other hand have one goal – to survive. Hedgehogs are small and slow, which would make them easy prey if it were not for the one big thing that they do better than any other animal. Hedgehogs have a very good defense, a shield of prickly spines that is their one big thing. If the hedgehog is attacked or frightened by a fox or any other predator, the hedgehog curls into a prickly and unappetizing ball. For the hedgehog, it is a matter of eating, sleeping, and having only one effective defensive tool, its spines.

Most businesses think that the fox would have the advantage when it comes to being the best. They are cunning and skillful. However, being like a fox can have negative effects on what the business is trying to achieve because foxes lack focus on the “one big thing”. A fox-aligned business is more likely to be scattered and inconsistent in its work, looking for a quick fix. The author argues that a hedgehog-aligned business would be the winner because they focus on one thing that sits at the intersection of what they’re good at, what drives their engine, and what they care about, which is the essence of the hedgehog concept, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

The Hedgehog Concept Defined

The hedgehog concept is not a strategy or goal but rather an understanding of what will make your business great compared to every other competitor in your industry. Companies both big and small need to understand the hedgehog concept if they ever hope to move from just being a good company to a great one.

To apply the hedgehog concept to your business, you need to ask three questions:

- What is your business already best at or can become best at?

- Where is your business generating the most revenue?

- What is your business passionate about?

You can create a three-ring Venn diagram to plot the answers to your questions.

At the intersection of all three circles is your hedgehog. The one thing that will transform your business from good to great.

Best At

The first circle in our hedgehog concept Venn diagram is what you can be the best at. Let me be clear, this is not what you hope to be the best at or what you aim to be the best at, but what you actually are already best at or can very easily become best at if you focus your energies when compared to your peers.

To understand what you are best at, you must also understand what you don’t do best. Too many businesses think that if they diversify their offerings this will provide more sources of revenue. The problem with this practice is that it dilutes the business’s efforts and hurts its brand. So when it comes to defining what you are best at it often means eliminating, or reducing your focus on some areas and increasing or even creating new offerings to find that new patch of blue ocean where you can be the best at something.

Related Post: The 4 Dimensions That Will Transform Your Business Model (Eliminate, Reduce, Increase Create)

A business needs to understand that doing what they are good at will only continue to allow the business to run with the good crowd, and not allow it to transcend to greatness. Focusing solely on what you already do or can potentially do better than your competitors is what has the potential to make your company great.

Jim makes it clear in his book that being great at something is not the same as the company’s core competency. Just because a business has been doing something for decades doesn’t mean they are the best at it.

For example, If your core competency is general landscaping but the industry is saturated with other much better run and well-financed landscaping companies you are unlikely to ever be the best general landscaping company in your geography. Better to find that slice within your industry that you can become the best at, such as zero-scaping, water feature landscapes, etc.

To become a hedgehog, it’s not about what you want to be the best at, because every business wants to be the best; to achieve hedgehog understanding you have to identify what you are or can be the best at and making the conscious decision stick to that one thing without distraction.

Example: Let’s compare the grocery chains Kroger and A&P. Both grocery chains bumped along as totally average performers in the grocery store industry for decades. Both A&P and Kroger had access to the same resources and saw that the American consumer was changing. The old grocery store business model was slowly becoming extinct. While A&P lurched from one faddish strategy to the next, like the fox, looking for a quick fix, Kroger made one bold and sweeping decision based on what their customer research uncovered and what it knew they could do better than anyone else in their industry.

Kroger adopted the concept of what is now known as the combination store. Rather than sell just groceries, Kroger shifted focus and offered customers the advantage of one-stop shopping. Kroger expanded its store footprint and offered customers a wide selection of consumables in addition to groceries. They added products related to health care, general merchandise, as well as pet care offerings. They added departments such as a pharmacy, a florist, a bakery and partnered with businesses to add a fuel center and a bank. While Kroger’s single focus on being a one-stop combination store made it the best of breed, A&P fell further behind and eventually filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Kroger ultimately outperformed the market by 10 times and its combination store concept has become the industry standard.

Economic Engine

The second circle in our hedgehog concept Venn diagram is what drives your economic engine. Your economic engine is how your business generates and sustains a robust cash flow and profitability.

A business needs to understand what are its Revenue Drivers by answering the following questions:

- For what value are your customers really willing to pay?

- What do they currently pay for?

- How are they currently paying?

- How would they prefer to pay?

- How much does each revenue stream contribute to the business’s overall revenues?

What Jim and his team found was that great companies attained a deep understanding of the key drivers of their economic engine and built their system in accordance with this understanding.

A quote from Good to Great:

“Think about it in terms of the following question: If you could pick one ratio (profit per X) – to systematically increase over time, what X would have the greatest and most sustainable impact on your economic engine?”

Good to Great

Considering your business, if you could have just one economic denominator per X, what would it be?

One company may have a denominator of Profit per Employee, another Profit per Economic Region, another Profit per Customer, and another Profit per Product Line. There is no predetermined right answer for all companies. Each business has to discover its own right denominator that drives its specific engine.

Having a single denominator however is not the point, the important thing here is that in your quest for a denominator, the process will lead to a deeper insight into what drives your economic system.

Example: In the highly competitive passenger airline industry, where most airlines measure Revenue per Seat, Profit per Seat, or Profit per Mile, Southwest Airlines bucked the system and set their denominator at Profit per Aircraft.

Let’s consider the implications of a Profit per Aircraft metric. To achieve the highest Profit per Aircraft, Southwest Airlines needed to look at pricing, frequency of flights, customer service, customer loyalty, airport turnaround times, maintenance costs, routing, etc. All of these aspects impact the company’s Profit per Aircraft and reflects the performance of its strategy.

In another example, Walgreens switched from Profit per Store to Profit per Customer Visit. By increasing Profits per Customer Visit, they were able to increase convenience and profitability throughout their entire system. Profit per Store would have been contrary to the idea of convenience.

Social Enterprise

Social enterprises are different as compared to for-profit companies and as such can’t have an economic denominator of profit per x. Whereas money, or more accurately profit, is an output in for-profit enterprises money is an input in a social enterprise. Social enterprises exist to meet social objectives, human needs, and national priorities that cannot be priced at a profit. When it comes to social enterprises like the Red Cross or organizations such as SCORE or the SBDC, where I volunteer much of my time, the circle related to “Economic Engine” is replaced with “Resource Engine“.

The resource engine of a social enterprise is composed of three components:

- Financial Capital – as in sustained cash flow from sponsors, donations, and contributions from the public.

- Human Capital – as in how well can you attract and retain quality volunteers.

- Brand Capital – as in the confidence that people have in the organization to provide the best return for monetary contributions or time contributed to the cause.

For a social enterprise the critical question is not “How much money do we make?” but “How can we develop a sustainable resource engine to deliver superior performance relative to our mission?”

Passion

The last circle in our hedgehog concept Venn diagram is what you are deeply passionate about. It’s important to note that it’s not about trying to create a passion, but rather discovering it. What is your business deeply passionate about? Nothing great can happen without passion. If you’re not passionate, you will not stick to your hedgehog concept when you encounter obstacles and therefore you will not have the energy and fortitude to do what it takes to transcend from good to great.

Passion is something that is deep and genuine and it’s an essential part for businesses to thrive doing what they do. Your passion is based on your “Why” and manifests itself in your company’s “Noble Purpose”. You can’t manufacture passion or motivate people to feel the passion. You can only discover what ignites your passion. You either have it or you don’t.

Example: Gillette chose to build sophisticated relatively expensive shaving products rather than fight a low-margin battle producing disposables because they just couldn’t get excited about cheap disposable razors. While most of the competitors like Warner-Lambert, Wilkinson Sword, and Schick courted acquisitions to enrich senior executives, board members, and shareholders, Gillette’s CEO fought off three hostile takeover attempts to focus on bringing the much more sophisticated Sensor and Mark3 razors to market that Gillette truly believed in. By the way, Jim calls this level of leadership to a cause greater than oneself the fifth level leadership.

Hedgehog Concept Execution

There is nothing wrong with understanding only two of the three circles, as it will lead to a good company. However, to achieve a great one, you have to understand all three. The essence of the hedgehog concept is when you find the intersection of what you can be better at than anyone else, what best drives your economic engine, and what you are passionate about.

If you make a lot of money doing what you can never be the best at, you’ll only build a successful business but not a great one.

If you’re the best at something but don’t have a passion for it, you’ll never remain on top.

And finally, if you only have a passion for something but you can’t be the best at it or it doesn’t make economic sense, it’ll be a lot of fun, but you won’t produce great results.

According to research by Jim and his team, once you find out how all three circles overlap and work out what the sweet spot in the middle looks like, then you have the insight to know what to specialize and focus on to grow your business from just being a good company to a great one.

When you think about your company, is it more like a hedgehog, focused on constant improvement of a single concept – your one thing – or a fox, constantly trying the next big thing?