Recently, I had the opportunity to discuss profit margins with a client. I shared how some companies can have higher margins than similar companies based on economies of scope. The client was confused about the differences between economies of scope and economies of scale. This post endeavors to describe how they are different and how that knowledge can unmask ways for a business to lower their average total cost, leading to higher profit margins.

What are Economies of Scale?

A common term used in business is “economies of scale”. Unfortunately, it is often used incorrectly to refer to economies of scope which is different. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Specifically, economies of scale are gained simply by selling more of a specific product. The desired outcome for many manufacturing businesses is the need to scale up production capacity for a successful product. Often, when a new product is introduced, the manufacturer uses a manufacturing line with limited production capacity or a co-packer until they see that the product has some traction in the market. Once the market success of a product is established, the manufacturer looks to scale up their production capacity to meet market demand for the product. By creating a more efficient dedicated manufacturing process, they can reduce the cost per piece and sell at higher volumes. This ramping up production effort is known as economies of scale.

What are Economies of Scope?

Simply put, achieving economies of scope means adding additional products or services which leverage some of the company’s resources. By adding additional offerings, the overall company costs are reduced because the company can make better use of its existing infrastructure. When you have several products or services that can share some resources, it is more cost-effective for the business than offering each independently, because the fixed costs of these shared resources are distributed across multiple offerings.

For example, let’s say that you have an online store where you want to start selling products for people with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Even if you have only one product, such as a big print keyboard, you still have to develop a website, get a merchant account and pay monthly usage fees, secure space to store products, conduct market research to zero in on your niche, and a host of other one time efforts just to get the first product set up to sell online. All these startup efforts are indirect costs to the business. These costs have to be covered by the margin or by the difference between what you pay to buy the product wholesale and the retail price that you sell to your customers in your online store. The number of products that you have to sell to reach your break-even may be quite high since it has to account for all of the indirect fixed costs with one product.

However, when you add a second product such as a talking watch, you would increase your economies of scope because you would be able to use many of the things you developed for the first product rather than be forced to create them again. For example, you do not have to develop another website for the second product, just a landing page that describes the new product. Moreover, since your merchant account fees are a fixed monthly expense, you now get to spread that indirect cost across two products vs absorbing them in a single product. Because you can extend the use of your resources to sell additional products to your same target market, you can continue to drive costs down and increase profit margins.

If you manufacture a product, economies of scope are where you would add new products that can be produced and shipped using some of the same equipment and materials to make other products, thereby reducing your average unit costs. In a simple example, even if the manufacturing of two products takes two different manufacturing lines, you could use the same boxing and labeling machines to package the product and the same shipper to pick up and deliver your product to your customers, thereby spreading these costs across multiple products.

Co-Products

Economies of scope can also occur because the products are co-produced by the same manufacturing process. Co-products occur when the production of one good produces another good as a byproduct or as a side effect of the production process.

For example, fossil fuels were first used to replaced oil obtained from animal fats, such as whale blubber in oil lamps. Lamp oil derived from fossil fuels was actually kerosene and was extracted from crude oil. However, a barrel of crude oil had to be refined into its components parts to extract kerosene. Many elements make up a barrel of crude oil, but kerosene was the only acceptable component for lamp oil. In fact, many of the other products obtained from crude oil were extremely volatile, namely gasoline and if not factored out through the distillation process would have explosive consequences.

While kerosene represented less than 10% of the refined elements from a barrel of crude, gasoline represented 45%, and diesel another 25%. For oil refiners like JD Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, everything other than kerosene was a byproduct of production. Initially, there was no demand for most of the other elements, so refiners had to pay to have them disposed of. That was until Henry Ford perfected his automobile, which used an internal combustion engine that ran on gasoline. As a result, gasoline became a co-product that Standard Oil could sell to fueling stations in addition to its main product kerosene.

Complementary Products

Another way to achieve economies of scope is with the use of complementary products. For example, Native Americans used to plant corn, pole beans, and squash together to increase the yield of each crop while improving the quality of the soil. As complementary products, the corn stalks provided the structure for the beans to climb up, the beans helped fertilize the corn by introducing nitrogen into the soil, and the shade produced by the large squash leaves reduced the light near the soil, preventing weed growth.

Consider Apple’s iPod and iTunes as another example of economies of scope based on complimentary products. The sale of iPods helped sales of iTunes. Moreover, the concept introduced by iTunes where you could buy just one song as opposed to an entire album helped with the sales of iPods.

Shared Inputs

Economies of scope can also come from sharing inputs in the production process. For example, my son Hank runs the kitchen in a retirement facility. He can make chicken wings, French fries, doughnuts, and many other products using his deep fat fryer. The economies of scope are achieved since all these products use the same input of the deep fat frier and the cooking oil which is far more efficient than having dedicated devices for each product produced.

Economies of Scope Risk Dilution of Brand

A challenge in pursuing economies of scope is that unless the additional products or services are tightly related, you run the risk of diluting what your business is known for. Let’s take the example above regarding selling products for people with AMD. By focusing on the specific niche of products for individuals with AMD, you become known as the “go-to” source for products to help people with AMD. To continue to build your business, you could focus on selling more of what you already sell. That’s economies of scale as it preserves your brand identity as a site of products for people with AMD. But let’s say that you choose to grow your business by adding eyeglasses and contacts. While corrective lenses are still related to vision, these products are not necessary products that a person with AMD would purchase. Adding these additional products are related to economies of scope but might dilute your site’s brand. You would no longer be seen as a site just dedicated to people with AMD.

Remember, the riches are in the niches so it is better to be an inch wide and a mile deep than to try to offer more products that are less well connected to your brand.

The Pasta Sauce Wars

In the 1980s, there were two dominant players in the pasta sauce market. Ragu and Prego. Each pursued a strategy of economies of scale and had one flavor of pasta sauce that they put their full marketing weight behind as they fought over a single large slice of the pasta sauce market. They both ignored the smaller slices of specialty sauces offered by boutique producers.

Even though in blind taste tests people preferred Prego to Ragu, Prego was losing market share to Ragu. Prego decided to change their strategy from one based on economies of scale to one on economies of scope. As a result, Prego developed a whole line of pasta sauces. Since Prego was known for pasta sauce, offering several flavors didn’t dilute their brand message as a pasta sauce company.

The change of strategy by Prego from perusing economies of scale and competing head-to-head with Ragu to one that embraced the economies of scope changed their trajectory. With the success of Prego’s economies of scope strategy, it soon became evident to Ragu that they too had to offer horizontal segmentation and embrace an economy of scope strategy or continue to lose market share to Prego.

Conclusion

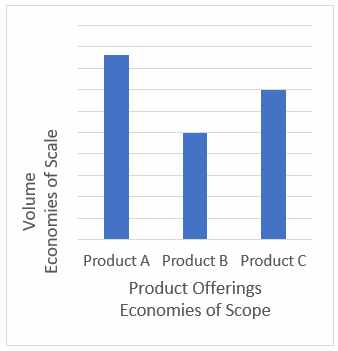

When I think of economies of scale, I think in terms of the sales volume and how high they are. When I think of economies of scope, I think of products that share production resources or how wide the offerings are.

There is no right or wrong answer when it comes to pursuing either a strategy of economies of scale or one of economies of scope. Each industry is different as is each company. The real lesson is to understand the difference between the two strategies and follow the strategy that is best for your company.

Is your business following a strategy of economies of scale or economies of scope?