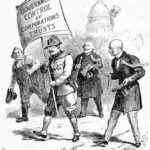

In the early 1900s, the United States found itself grappling with a cultural divide. On one side stood the saloon crowd—rough-and-tumble, working-class folks who found camaraderie, entertainment, and escape in the local watering hole. On the other side stood the Anti-Saloon Organization (ASO), a powerful political and social movement that believed alcohol was tearing apart the moral and social fabric of the nation.

The ASO wasn’t interested in moderating the behavior of saloon-goers—they were intent on eradicating alcohol entirely from American society. Rather than pushing for reform or regulation, the ASO championed total abstinence from alcohol. Their influence culminated in 1919, when they succeeded in passing the 18th Amendment, marking the beginning of the Prohibition era.

Related Post: From Saloons to Speakeasies: How a Rebrand Repealed Prohibition

The intent may have been noble—curbing alcohol abuse and promoting public health—but the strategy was extreme. The law criminalized the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcohol nationwide. Predictably, rather than solving societal problems, Prohibition gave rise to unintended consequences: the black market boomed, organized crime thrived, and enforcement agencies were overwhelmed and outgunned.

Eventually, the overreach of the ASO backfired. Their extreme stance inspired the rise of counter-movements, such as the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment (AAPA). Public opinion began to shift, particularly as the economic consequences of the Great Depression intensified. By 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing the 18th and officially ending Prohibition.

There are lessons here that extend far beyond alcohol policy, and they’re particularly relevant to business and negotiation strategy.

In business, taking an extreme position may feel like a bold move. It can provide a clear line in the sand, galvanize your team, and give you a moral high ground. But if you’re not careful, it can also rally your opponents, polarize stakeholders, and ultimately lead to your own undoing.

This is especially true in negotiations. Let’s say you’re trying to strike a business deal. If you take an inflexible, all-or-nothing stance, you might get what you want in the short term—but at the cost of goodwill, repeat business, or future cooperation. Negotiation isn’t about domination; it’s about finding mutual value. The best deals are the ones where both parties leave the table feeling like they’ve won something.

You can see echoes of this in modern politics, social debates, and even workplace dynamics. When one side pushes too hard for an extreme change without seeking understanding or compromise, the backlash often outweighs the initial gains.

Entrepreneurs and business leaders should take this historical lesson to heart: winning the battle doesn’t mean you’ve won the war. If your strategy alienates your team, customers, or partners, the long-term damage might be worse than the short-term win.

Instead, consider a more balanced approach. Explore alternatives, listen actively, and find alignment where possible. That doesn’t mean you abandon your principles—it means you advance them in a way that encourages collaboration, not confrontation.

Are you pushing an extreme position in your business dealings? If so, what might it cost you in the long run?